Though our official journey began in 1983, the heart of our story traces back to the bustling music scene of 1930s New York City.

Is Everybody Happy?

In the 1930s, just as it is today, New York City was a Mecca for musicians. Midtown Manhattan was alive with music, from the innovative saxophone of Charlie Parker to the grandeur of the New York Philharmonic under the direction of Maestro Arturo Toscanini. Though not quite in that elite class as a performer, Charles Ponte was an accomplished English hornist with the Radio City Music Hall Orchestra. He also played with the big bands of Paul Whiteman, Les Brown, and Ted Lewis. His rich saxophone sound and skill with the elusive double reeds made him well-known among NYC musicians of the 1930s and 1940s.

Charlie played with or befriended many of the greats: Lester Young, Sonny Rollins, Miles Davis, Harold Gomberg, Samuel Baron, and countless other world-class musicians across all genres. He formed a close bond with fellow musicians Benny Fairbanks and Sam Shapiro, with whom he performed in major big bands. The three of them appeared together as members of the Ted Lewis Band in the Abbott and Costello classic “Hold That Ghost.” Charlie, with Ted Lewis in the 1950s, became famous for his tagline, “Is Everybody Happy?”

Charlie and all his instruments with Ted Lewis in the 1950’s. His famous tagline was “Is Everybody Happy?”

Anybody Got A Dime?

From the 1930s through the 1970s, West 48th Street, between 6th and 7th Avenues, was the place to be for top woodwind repairmen and music stores catering to professionals in Manhattan. With Broadway theatres, Carnegie Hall, and later Lincoln Center nearby, it was a natural gathering spot for musicians between shows.

Charlie, Benny, and Sam loved performing, but the road and late-night gigs disrupted their home lives with their new families. They dreamed of opening a music store on 48th Street, focusing on woodwinds and strings, but the demands of big band road tours kept pulling Sam and Benny away. Charlie, however, stayed in New York, playing at Radio City and nurturing the idea of a store.

The inscription on this photo reads: “To Charles Ponte, with my heartiest good wishes, Sincerely, Jean Harlow. Anybody got a dime?”

Here’s An Oboe, Learn To Play It

Not long after, Charlie rented a small space on West 48th Street from Linx and Long, a well-established woodwind music store. He began selling whatever instruments he could buy and fix. Known and loved by half the musicians in New York, his shop quickly became a hub for premier players. Soon, hordes of younger musicians, who emulated these greats, followed.

Among those younger musicians were some who would become giants in the music world. One often-repeated story, confirmed by the player himself, involves a young musician who was trying to break into the scene on clarinet but wanted to double on oboe. Lacking the funds to buy one, he casually mentioned this to Charlie, expecting only sympathy. Instead, Charlie handed him a brand-new Ponte brand oboe, saying, “When you make your first money with this oboe, then you think about paying for it. Till then—practice.” That young musician was Phil Bodner, who became one of the finest doublers ever to play in New York. Bodner’s credits include performances with everyone from Sinatra to Steely Dan, as well as notable jazz gigs with Benny Goodman, the Gil Evans Orchestra with Miles Davis, Oliver Nelson, J.J. Johnson, and Bill Evans. They became lifelong friends.

Phil played the famous bass clarinet part on Steely Dan’s “Peg” with Wally Kane. He appeared on hundreds of renowned classic recordings and was very influential to me.

Brothers And Friends

As demand grew, Charlie expanded his offerings to include new instruments, accessories, double reed equipment, strings, guitars, tubas—anything and everything musical. His shop rapidly outgrew the Linx and Long space. In 1947, he rented his own store on West 48th Street, proudly displaying the “Charles Ponte Music Company” sign outside. Inside, the store housed an ever-growing collection of musical instruments, supplies, and parts.

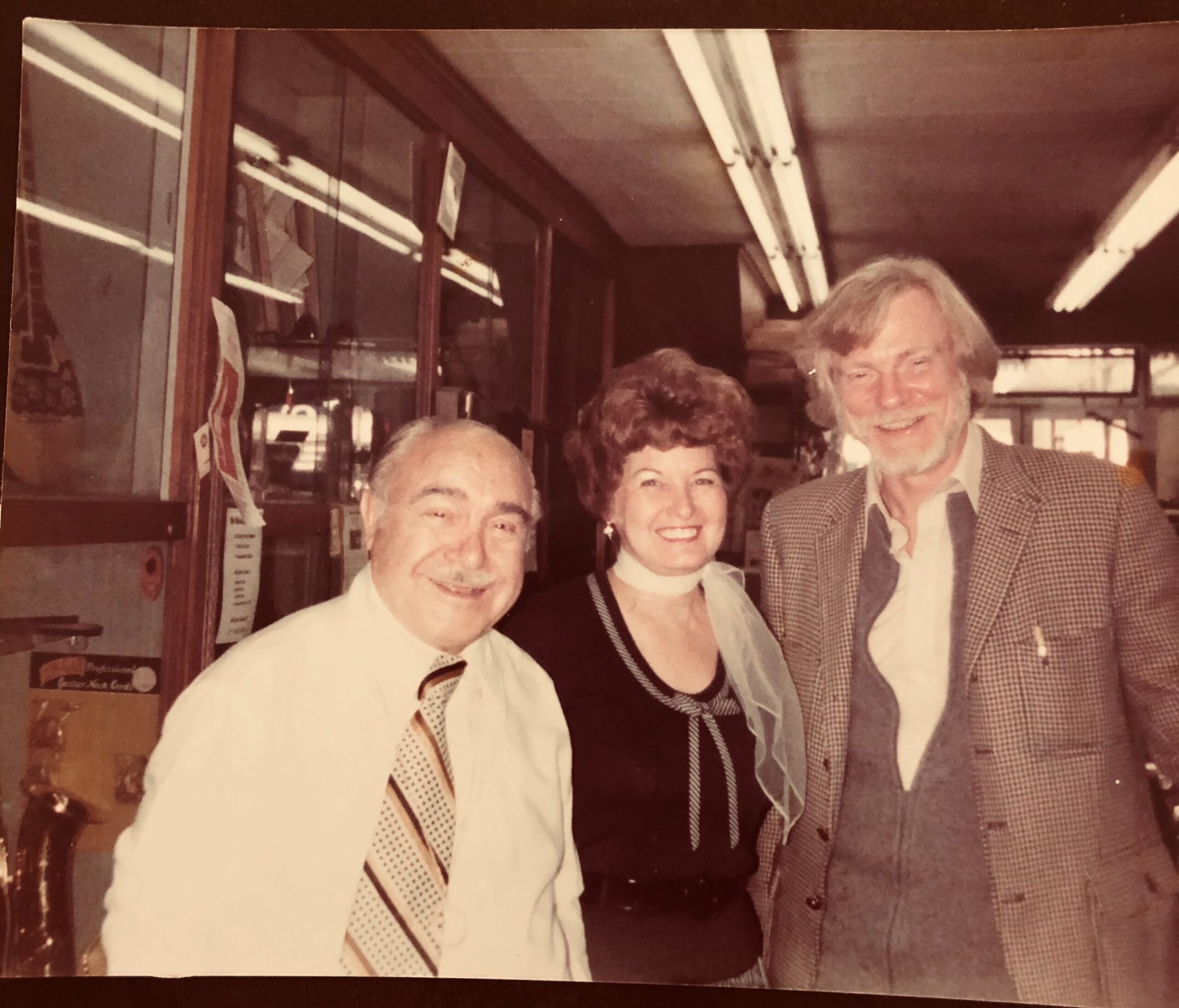

Around this time, Charlie’s younger brother Frank, a trumpet player, joined him. Benny and Sam, still on the road, eventually joined the team as well when the big band era began to wane. The store’s name remained Ponte’s, but the four were a close-knit team. The business grew exponentially, gaining an international reputation. Touring musicians from around the world would visit the “musician’s candy shop,” as it became known, bringing back word to their colleagues of this wonderful store run by and for musicians.

Charlie Ponte and Frank Ponte at Ponte Music Company in the 1970s.

Good Will

With the guidance of his friend, billionaire philanthropist Paul Mellon, Charlie Ponte donated instruments and gave jobs to Haitians as oboe and bassoon reed makers!

How Many Saxophones Can You Fit In A Basement?

Through the 1950s and 1960s, as development began to encroach on jazz’s famed 52nd Street and 48th Street’s Music Row, Charlie held his ground, growing his business in the same small four-story building with the storefront that he now owned. But eventually, with parking garages and office towers going up around them, most of the other stores were forced to relocate or close, including the venerable Linx and Long. Some, like Giardinelli’s and Sam Ash, sold to corporations.

The city offered Charlie incentives to move for the sake of development, including a five-story, 21-foot-wide building two blocks south on West 46th Street, right on the edge of Times Square. He reportedly paid just $1 to make it official. Several other long-time shops had moved to that block, preserving some of the old neighborhood’s character. Here, Charlie, Benny, and Sam continued to prosper, filling their store with instruments and friends.

The new shop, with a more spacious basement, allowed Charlie to stock dozens of high-end instruments for his professional patrons. The cramped basement was packed with Selmer Mark VI saxophones, top professional tubas, trombones, trumpets, and more. Top players, including Sonny Rollins and Gerry Mulligan, visited regularly to try out instruments.

Sonny Rollins visited weekly to try out instrument after instrument.

Gerry Mulligan was a regular.

Gerry Mulligan was a regular.

The Ponte Knife (Now The Charles Knife)

Merrill Greenberg on tour in India. He was English Hornist with the Israeli Philharmonic for over thirty years.

Transitions

Jerry Roth was 2nd oboist (ret.) of the New York Philharmonic, a founding member of the New York Philharmonic Woodwind Quintet, a great oboist, and a gifted teacher.

The 11th Avenue Police Impound Lot

One afternoon, during my first semester, I drove my father’s prized gold Rambler American to the city and parked in front of Ponte’s while picking up my oboe from repairman Pedro Rivera. I walked to the back of the narrow store, where Charlie and Gomberg were talking. Recognizing my oboe—his old one—Gomberg asked me to play it right there to test it out. For 15 minutes, we took turns playing Loree #BI-37, with Pedro making minor adjustments. I was in awe of Gomberg’s playing, but as I walked him to the door, I realized with a sinking feeling that my car had been towed.

Hours and dollars later, I retrieved the car, exhausted but with a great story to tell.

When Harold Gomberg called my parent’s home looking for me, he would announce himself to my mother by saying “This is Harold Gomberg of the New York Philharmonic”. Here seen with his brother Ralph, who also studied with Tabuteau, and led a highly successful career as principal oboe of the Boston Symphony.

10,000 Reeds

When Gomberg left, I went back into the store to call and track down the car. Charlie approached and shocked me by asking if I was interested in a job making reeds in his shop. As most double reed players view reed-making as a necessary evil, I hesitated and asked for a day to think it over. My dad thought it could be good, as long as it didn’t interfere with my studies. “And by the way,” he asked, “how’s my car?”

You can guess the rest: I took the job, and over the next five years, I made thousands of reeds and learned more than I could have ever imagined. I worked three days a week, seven hours a day, while continuing my studies. It left little time for anything else, but I was over the moon.

Fired And Hired And Fired And Hired

The following summer, I started my solo playing career as oboe soloist with the Long Island Youth Orchestra on a six-week tour of countries bordering the Indian Ocean. Charlie, furious that I would be away for six weeks, fired and rehired me twice before I left. On the last morning, he fired me again.

Six weeks later, I returned, tired but fulfilled from a successful tour. I showed up at the shop the next morning, and without a pause, Charlie told me I made lousy reeds and that I had better get back to work.

The Long Island Youth Orchestra performs worldwide.

The End Is The Beginning

In 1983, at the age of 85, Charlie decided it was time to retire. Slowed down by the years, he accepted an invitation from his daughter and her family in the Midwest to move in with them. As the shop’s activities wound down, his long-time companions—Benny, Sam, Charlie’s brother Frank (a trumpet player who ran the brass department), and Harry Nifik, the cranky sax repairman on the second floor—also decided to retire.

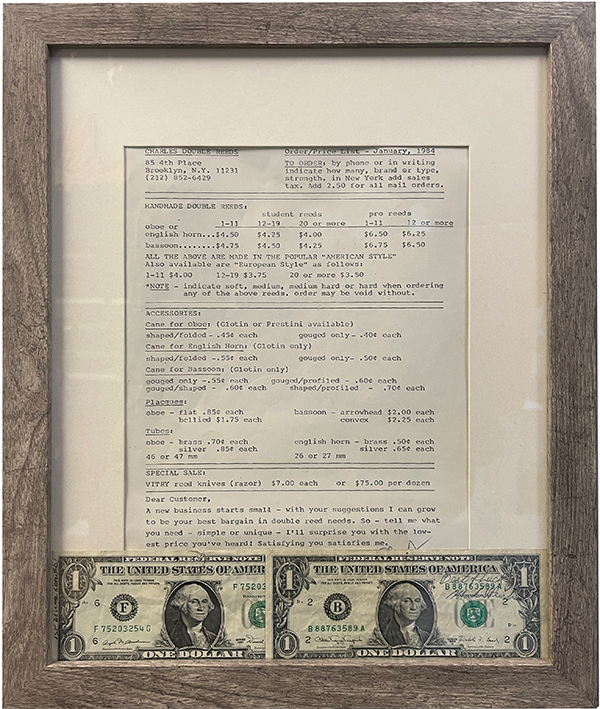

As for me, I was ready to move on as well, focusing on the performance career I had been building. But then, Charlie made me an unexpected offer: for a nominal fee, he would pass on the entire double reed side of his business for me to take on and make my own. It was a proposal I had never anticipated. I sought advice from family and friends, and my father-in-law, in particular, was adamant that I should seize the opportunity. He eventually convinced me, even loaning me the money and guiding me on how to start such an ambitious venture.

The Next Generation

Charlie had set aside the entire double reed department for me, allowing me to use his storefront for six months while he closed down the business and I found my footing. Juggling both a business and a music performance career was no small task, but I was determined. Just as the building was about to be transferred to its new owners (a Dominican fruit store), I took a leap of faith and transformed what had been a storefront for decades into a mail-order business. I renamed it Charles Double Reed Company and moved it to our living room in Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn. I relocated the cabinets, tools, products, and all the double reed supplies into the now-overstuffed space.

Charlie retired to Indiana, where he lived with his daughter and her family until his passing in 1990. Charles Double Reed Company, starting with the names and addresses of 600 double reed players I had collected in those last six months at Charlie’s storefront, began to grow.

Back to New York City And Repair

Within a few months, the orders started pouring in, more than I could handle alone. Some double reed friends joined me, and together we became a wonderful team. The business quickly outgrew my living room, taking over the kitchen and bedroom. It was clear that Charles Double Reed Company couldn’t stay in my apartment much longer. Taking another leap of faith, I relocated the shop to a penthouse loft space on West 28th Street off Sixth Avenue in Manhattan.

We set up shop on the famed “Flower Block,” where the city’s hotels and well-to-do sourced their floral arrangements. It was a bustling street, active from 3 in the morning until late afternoon, and although we were in Manhattan, it felt like a safe and well-guarded location—and it smelled nice too.

The loft had a huge safe for the dozens of high-end instruments we now stocked and offered a stunning view from the Chrysler Building to the Empire State Building to the World Trade Towers. Double reed players from around the world visited us while touring New York, and members of every major symphony orchestra became customers and friends.

I had been repairing instruments as favors for friends for years, but word began to spread. Requests to replace pads or make small adjustments started coming in, and it became clear that this was a path worth pursuing. Having apprenticed under Pedro Rivera back at Ponte’s old shop, I began to seriously hone my skills in double reed repair—a craft I continue to refine to this day.

We Were Online Before Amazon, Seriously

After that initial flyer, it became evident that we needed a full catalog. At first, we created small ones with the help of a professional typesetter, as typesetting was the standard method for creating text on paper at the time. Eventually, we were producing a full-color, 50-page catalog every year, which we hand-stamped and mailed to our growing list of thousands of customers.

As technology evolved, our typesetter suggested I learn to create the catalogs myself on a computer. I invested in an IBM PC with a whopping 64K of memory and two floppy disk drives—cutting-edge at the time. I used a program called ImagePro, which later evolved into Photoshop, and transferred thousands of customer addresses from 3×5 index cards to a spreadsheet program called Lotus 1-2-3, the predecessor to Excel.

Around this time, I became fascinated by HTML, the coding language for websites, and recognized the potential of the internet to replace printed catalogs. We were fortunate that the first to embrace online purchasing were the military and universities, both large buyers of double reed instruments and reed-making materials. I became proficient in HTML and other coding languages and launched a simple two-page website for Charles Double Reed Company. Within months, I had figured out how to accept orders via email, a rudimentary process through AOL. Soon, “you’ve got mail” also meant “you’ve got orders.” We were fully online selling double reeds and instruments by 1992, a full three years before Amazon first accepted online orders.

So There I Was

In the following years, the internet became our primary sales and communication channel, accounting for about 85% of our orders. As our lease on the business space in Manhattan was ending, and with my partner Sarah and I considering a change, we made a bold decision: we renewed the business lease but sublet the space, dropped our apartment lease, and Sarah gave notice at Waverly Fabrics. We then jumped off a proverbial cliff and landed in beautiful North Conway, New Hampshire. My next catalog and the website featured the new address, Sarah joined the business, and we were going full speed in short order.

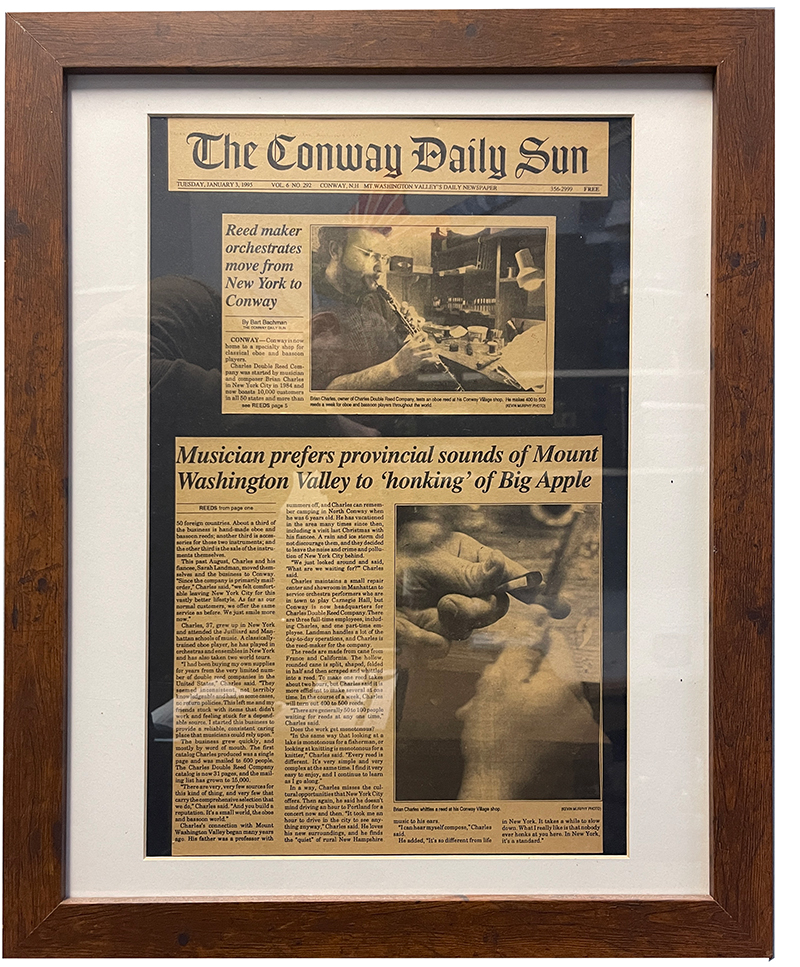

We were welcomed with open arms in the North Country and even made the front page of the local newspaper. We’ve been in North Conway for about 30 years now. It’s a stunning, four-season resort area with seven nearby ski resorts and a thriving music scene. Visitors often stop by to try instruments and then explore the area’s hiking, skiing, or tax-free outlet shopping.

Another Music Shop

Over the years, local residents from the Mount Washington Valley would come to our double reed store hoping to find guitar strings, clarinet reeds, and other basic musical supplies. Recognizing this unmet need, I started a second music store called North Conway Music Center. While not my first love, the store offered all the essentials for local performers, teachers, and schools, including band instrument rentals, lessons, repairs, and a wide selection of guitars, brass, keyboards, and more. I modeled it after the full-line music stores of 48th Street in New York City. With no other full-line store within a 50-mile radius, the shop thrived.

I also took on the task of learning to repair instruments beyond double reeds, eventually training apprentices so I could refocus on oboe and bassoon. After 15 successful years, I sold the second shop to the manager, who continues to run it proudly, providing essential goods and services to local musicians, students, and visitors to the Mount Washington Valley area of New Hampshire.

As of early 2024, both North Conway Music Center and Charles Double Reed Company are thriving and share the same location.

There’s More To Come

Brian Charles

Founder/Director, reedmaker, repair tech, appraiser

Charles Double Reed Company

We are VERY interested in acquiring photographs and memorabilia from the heyday of New York’s Tin Pan Alley, 52nd Street Jazz Scene, and West 48th Street Music Row. If you have anything or can provide a lead, please contact brian@charlesmusic.com